Casino Music Performance Proposal

- Casino Music Performance Proposal

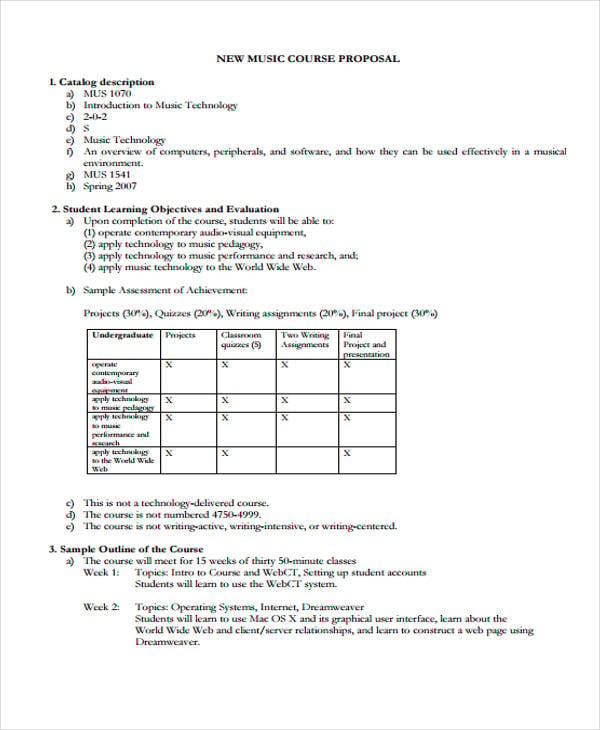

- Casino Music Performance Proposal Sample

- Casino Music Performance Proposal Examples

Special Feature

If you’ve ever ventured into a casino, you will realize that music is one of the biggest influences on the guests who enter these exciting venues. While some myths will suggest that casinos use music to lead people into staying fixated on the games that they are playing, one thing that music does do in the casino is enhance the player’s experience, by allowing them to enjoy themselves. One of the many things that all music genres in casinos have in common is that they are exceptionally upbeat and exciting, in order to allow the customer to have a good time as soon as they’re in their seat, rather than focussing on the blackjack myths or poker legends that are stopping them from enjoying the game. Setting the mood is an exceptionally important part of the casino, and because of this more people are likely to spend more money if they’re listening to an upbeat song as opposed to a love ballad. Here, we’ve done a little bit of research to find out exactly what type of music is played in the casino, and who picks them.

Las Vegas

One of the most notable things about Las Vegas casino resorts, is that more often than not, they will have a resident musician playing at their casino night after night. Whether it’s the like of Calvin Harris or even Celine Dion, there’s a huge number of artists that you can find there. However, that isn’t the only thing that they rely on when it comes to music in their casino, because without a little background music, the atmosphere of the casino floor would actually be a little dull. In the Palms Hotel, there is plenty of music that are chosen, and it turns out that CEO and president of the Palms, Hotel Todd Greenberg, personally selects a lot of the music on the playlist, alongside some of his trusted colleagues, in order to give guests a huge list of music to listen to rather than the same 20 track playlist played on repeat. He has been quoted saying that he wants “music to be fun, interesting and accessible to everyone” and that he tries to emulate the process of a film’s soundtrack “to help maximise their casino experience.”

Concept images of the resort casino, hotel, and multi-purpose performance venue. How many jobs will be created? It is estimated that Durham Live will create up to 10,000 jobs, and the Pickering Resort Casino alone is expected to see approximately 2,000 new jobs for the casino, hotel and performance. A performance management conference focused on the company’s future. Leadership Team Performance Plan. PDF; Size: 70 KB. 10 Essential Steps for Writing a Formal Proposal. There are times that we dread the very thought and act of writing a proposal. However, there is a way out of that gnawing feeling of.

This is a simple band performance contract for small shows. It includes the all-important free tix, parking, and munchies/water. Please note the mandatory sound check of Venue's systems - the Band needs to take the lead in setting that up. Disputes are settled by inexpensive arbitration. Bands may prefer to use a small claims court in their hometown. I also recognize that this proposal does not address some of the issues raised in the proposals that music industry representatives have recently submitted to you. Some of those issues relate to ringtunes, promotional uses, multi-format discs, percentage royalty rates, lyric displays, licensing of music for audiovisual works, locked content. Moonglow Love Theme From Picnic (1955) Written by Edgar De Lange (as Eddie DeLange), Will Hudson, Irving Mills / Morris Stoloff Courtesy of MCA Records Published by EMI Mills Music, Inc./Scarsdale Music Corp. Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., Inc. Film Division.

Lounge Music

During the day, during quieter times, some casinos may play what’s known as lounge music, which was popular in the 1950s and 1960s. This is defined by its easy listening qualities, and while the night-time experience may want to create a party atmosphere in the casino through upbeat music, during the day some people many people may want to have something more relaxing while they are casually gambling in the casino, or walking through the hotel in order to find the pool.

Music is a huge marketing tool in the casinos, and while the myths of hypnotic music aren’t totally true, music really can help to change a guests’ attitude, in order to provide the very best atmosphere for the guests. This helps to boost the guest’s experience and as a result they may stay for longer and spend more money.

United States House of Representatives

109th Congress, 1st Session

June 21, 2005

Music Licensing Reform

Mr. Chairman, Mr. Berman, and distinguished members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to appear before you to testify on reform of Section 115 of the Copyright Act, which governs the licensing of the reproduction and distribution rights for nondramatic musical works. As I have previously testified, the present language of Section 115, with its compulsory license to allow for the use of nondramatic musical works for the making and distribution of physical phonorecords and digital phonorecord deliveries, is outdated. Reform is necessary, and I am pleased that you have asked me for my recommendations on how to amend Section 115 to facilitate the licensing of nondramatic musical works in a way that will serve the interests of composers and music publishers, record companies and other providers of recorded music, and the consuming public, especially with respect to digital audio transmissions of music. My proposal addresses many of the problems that are currently hindering much, if not all, of the music industry and digital music services in their efforts to make a wide variety of music available to the listening public and to combat piracy.

Background

Almost a century ago, Congress added to the Copyright Act the right for copyright owners to make and distribute, or authorize others to make and distribute, mechanical reproductions (known today as phonorecords) of their musical compositions. Due to its concern of potential monopolistic behavior, Congress also created a compulsory license to allow anyone to make and distribute a mechanical reproduction of a musical composition without the consent of the copyright owner provided that the person adhered to the provisions of the license, most notably paying a statutorily established royalty to the copyright owner. (1) Although originally enacted to address the reproduction of musical compositions on perforated player piano rolls, the compulsory license has for most of the past century been used primarily for the making and distribution of phonorecords and, more recently, for the digital delivery of music online.

At its inception, the compulsory license facilitated the availability of music to the listening public. However, the evolution of technology and business practices has eroded the effectiveness of this provision. Despite several attempts to amend the compulsory license and the Copyright Office's corresponding regulations (2) in order to keep pace with advancements in the music industry, the use of the Section 115 compulsory license has steadily declined to an almost non-existent level. It primarily serves today as merely a ceiling for the royalty rate in privately negotiated licenses.

1. Last Year's Hearing.

Last year, on March 11, this Subcommittee conducted a hearing on “Section 115 of the Copyright Act: In Need of an Update.” That could be the theme for today's hearing as well. A number of witnesses testified last year about the difficulties they have in licensing the use of nondramatic musical works under this antiquated statutory scheme. Among other things, complaints were voiced about the difficulties in locating copyright owners to obtain licenses to reproduce and distribute nondramatic musical works; the procedural requirements for obtaining a compulsory license; the lack of clarity over what activities are covered by the compulsory license; difficulties in licensing the use of nondramatic musical works for sound recordings in new configurations; and problems created by the per-unit penny-rate royalty established by Section 115.

Two of the issues highlighted at that hearing - issues that we at the Copyright Office have been hearing about for several years - involve problems arising when online music services wish to license activities that involved both reproduction and public performance, leading to demands for payment to two separate agents for the same copyright owner; and the contrast between the relatively efficient licensing process for performance rights and the unsatisfactory process for licensing reproduction and distribution rights. While the three performing rights societies - the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (“ASCAP”), Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) and SESAC, Inc. — collectively are able to license public performances of virtually all nondramatic musical works, the main licensing agent for the reproduction and distribution rights - the Harry Fox Agency, Inc. (“HFA”) — is unable to license a significant percentage of nondramatic musical works. For this and other reasons, some of which I will address below, online music services that wish to obtain licenses to make available as many nondramatic musical works as possible find it impossible to obtain the necessary reproduction and distribution rights.

As Cary Sherman, the President of the Recording Industry Association of America (“RIAA”), testified last year, “if the overall purpose of Section 115 was to ensure the ready availability of musical compositions, that objective is no longer being achieved.”

At last year's hearing, I set forth several legislative options for this Subcommittee to consider to address the problems that had been identified with respect to the existing Section 115. The first option, which forms the basis of the Copyright Office's current proposal, was to eliminate the Section 115 compulsory license. A fundamental principle of copyright law is that the author should have the exclusive right to exploit the market for his work, except where doing so would conflict with the public interest. While the Section 115 statutory license may have served the public interest well with respect to the nascent music reproduction industry after the turn of the century and for much of the 1900's, it is no longer necessary and unjustifiably abrogates copyright owners' rights today. Virtually all other countries have eliminated similar compulsory licenses in favor of collective administration, and so should the United States. Domestic performing rights organizations, such as ASCAP, BMI and SESAC, have already proven that collective licensing can and does succeed in this country. Moving towards a system of private, collective administration would restore the free marketplace as well as bring the United States in line with the global framework in which digital transactions must necessarily operate.

Recognizing that parties with stakes in the current system may resist this concept, I also suggested several other legislative options for consideration. These options would retain the statutory license, but would amend the language of Section 115 to address specific problems which have arisen to date. Among the options I identified were:

Clarification that all reproductions of a nondramatic musical work made in the course of a digital phonorecord delivery (“DPD”) are within the scope of the Section 115 license.

Amendment of the law to provide that reproductions of nondramatic musical works made in the course of a licensed public performance are either exempt from liability or subject to a statutory license.

Expansion of the Section 115 DPD license to include both reproductions and performances of nondramatic musical works in the course of either digital phonorecord deliveries or transmissions of performances.

I also identified proposals made by various interested parties, some of which would involve major revision of the law and others of which would involve tinkering with the details of the Section 115 compulsory license to make it more workable, including:

Adoption of a model similar to that of the Section 114 webcasting license, requiring services using the license to file only a single notice with the Copyright Office stating their intention to use the statutory license with respect to all nondramatic musical works.

Establishment of a collective to receive and disburse royalties under the Section 115 license

Designation of a single entity, like the Copyright Office, upon which to serve notices and make royalty payments.

Creation of a complete and up-to-date electronic database of all nondramatic musical works registered with the Copyright Office.

Shifting to the sound recording copyright owner the burden of obtaining the rights for online music services.

Creation of a safe harbor for those who fail to exercise properly the license during a period of uncertainty arising from the administration of the license for the making of DPDs.

Extension of the period for effectuating service on the copyright owner or its agent beyond the 30 day window specified in the law.

Provision for payment of royalties on a quarterly basis rather than a monthly basis.

- Provision for an offset of the costs associated with filing Notices with the Office in those cases where the copyright owner wrongfully refuses service.

Although some of these options may still be viable, my testimony today focuses on the elimination of the statutory license in favor of marketplace collective administration because that is the solution I believe is most likely not only to remedy today's problems, but perhaps more importantly, also to provide a workable solution for tomorrow's issues. Moreover, it is the solution that comports with the Copyright Office's longstanding policy preference against statutory licensing for copyrighted works and our preference that licensing be determined in the marketplace where copyright owners exercise their exclusive rights.

2. Regulations Regarding Notices of Intention to Use the Section 115 License.

However, before describing my current proposal for reform, I would like to summarize developments since the hearing in March of last year. In June 2004, I issued final regulations to reform the process for serving and filing notices of intention to use the Section 115 compulsory license. (3) Previous regulations required that a person wishing to make use of the compulsory license must serve a separate notice, for each nondramatic musical work to be licensed, on the owner of the copyright of that nondramatic musical work. Under the new regulations, a licensee may serve a single notice for any number of nondramatic musical works on a copyright owner or the agent of the copyright owner, so long as the enumerated works are owned by that copyright owner. The new rules require the copyright owner or agent receiving the notice to notify the licensee promptly where to send royalty payments. Finally, the rules resolved a dispute over whether a licensee who has already served or filed a notice of intention to use a particular nondramatic musical work must submit a new notice of intention to use the compulsory license whenever the licensee begins to offer that work in new configurations. For example, must someone who has served a notice of intention to issue traditional phonorecords of a nondramatic musical work serve a new notice of intention in order to offer that work by means of digital phonorecord deliveries? The new rules provide that no new notice is required. The rules also streamlined the notice of intention process in other minor respects.

3. Discussions Regarding Legislation

While our efforts on the regulatory front have made some progress in making the Section 115 compulsory license easier to use, they have not addressed the fundamental problems with the license because those problems — based in the statutory framework — are beyond my power to cure by regulation.

You recognized that last July, when you asked me to bring interested parties together to address the modernization of Section 115. (4) You asked that I survey areas of concern, identify areas of agreement, and identify the positions of various parties on areas where there was no agreement. To the extent that there was agreement, you asked that I draft model legislative language reflecting that agreement. I was asked to report on the results of these efforts in September.

Discussions involving the National Music Publishers' Association, Inc. (“NMPA”) and its subsidiary The Harry Fox Agency, Inc. (“HFA”), the Digital Media Association (“DiMA”) and the Recording Industry Association of America, Inc. (“RIAA”) were held through last summer, but unfortunately they were not as productive as we had hoped they would be. On September 17 I reported to you that the parties were willing to explore legislation to establish a blanket licensing scheme in Section 115 to facilitate the licensing of copyrighted nondramatic musical works, but that there were significant differences among the parties regarding the appropriate scope of such a license and regarding operational and economic issues. (5) The good news was that the key parties were willing to consider a blanket license that, similar to the licenses for performance rights offered by organizations such as ASCAP and BMI, would relieve licensees of the burden of seeking separate licenses for each nondramatic musical work they wished to use. But on issues such as the scope of the license, the royalty rates and terms, and other issues, the parties were far apart.

My letter noted that the parties were willing to continue discussions in an effort to arrive at consensus legislation. I understand that discussions among the parties have continued to this day, although with no direct involvement by the Copyright Office, and in recent weeks various organizations representing publishers, songwriters, performing rights societies, record companies online music services, and record retailers have come to you with their separate proposals on how to reform Section 115. In general, those proposals appear to reflect the same disparity of views that I reported on last September.

The Need for Reform

There is no debate that Section 115 needs to be reformed to ensure that the United States' vibrant music industry can continue to flourish in the digital age. As evident from the numerous proposals for change recently submitted to you, Mr. Chairman, by entities representing all aspects of the music industry, the operative question is not whether to reform Section 115, but how to do so. Prior attempts to tinker with Section 115's language to include online transactions have been useful band-aids, but ultimately required Congress to continue to revisit the same issues as technology and business realities have changed the context.It is now time to modernize Section 115 holistically not only to address immediate needs, but also to establish a functional licensing structure for the future.

Section 115 and its predecessor have rarely been used as functioning compulsory licenses. Rather, it has served simply as a ceiling on the royalty rate in privately negotiated licenses. As such, it has placed artificial limits on the free marketplace. Until the digital revolution in the mid-1990's, the system worked well enough, although — as I recounted in my testimony last year — the Copyright Office long ago proposed its elimination. As long as the function of Section 115 was simply to set the rates for licenses between music publishers and record companies that wished to make and distribute sound recordings and to provide a rarely-used backup procedure for obtaining licenses, there was no compelling need to change the system. But with the rise of digital music services that seek to acquire the right to make vast numbers of already-recorded phonorecords available to consumers, Section 115 is not up to the task of meeting the licensing needs of the 21st Century. A new mechanism is needed to make it possible quickly and efficiently to clear the several of the exclusive rights of copyright for large numbers of works.

Our compulsory license in the United States is an anomaly. Virtually all other countries which at one time provided a compulsory license for reproduction and distribution of phonorecords of nondramatic musical works have eliminated that provision in favor of private negotiations and collective licensing administration. Collective administration has proven successful, and in many countries these organizations license both the public performance right and the reproduction and distribution right for a musical composition, thereby creating more efficient “one-stop-shopping” for music licensees and streamlined royalty processing for copyright owners. (6)

The United States also has collective licensing organizations, such as ASCAP, BMI and SESAC. However, consent decrees have limited some of the domestic collective organizations' abilities to license both rights. Similarly, the existing Section 115 limits other licensing entities' negotiating positions with respect to reproduction and distribution rights. The domestic music licensing structure for nondramatic musical works has thus evolved as a two-track system, one for licensing public performance rights and the other for licensing the reproduction and distribution rights. The reality of digital transmissions, though, is that in many situations today it is difficult to determine which rights are implicated and therefore whom a licensee must pay in order to secure the necessary rights. Faced with demands for payment from multiple representatives of the same copyright owner, each purporting to license a different right that is alleged to be involved in the same transmission, licensees end up paying twice for the right to make a digital transmission of a single work. Some have called this “double-dipping.” I would not characterize it that way; I recognize that separate rights are involved — or at least alleged to be involved — and that separate licensors exist for each of those rights. But whether or not two or more separate rights are truly implicated and deserving of compensation, it seems inefficient to require a licensee to seek out two separate licenses from two separate sources in order to compensate the same copyright owners for the right to engage in a single transmission of a single work.

The existing Section 115 provides so little guidance for this present problem that the Recording Industry Association of America (“RIAA”), the National Music Publishers' Association, Inc. (“NMPA”) and The Harry Fox Agency, Inc. (“HFA”) have entered into a licensing agreement for any reproduction and distribution rights implicated in a performance of a musical composition through an on-demand stream, even though it is debatable whether such a transmission even involves a compensable reproduction. Meanwhile, the ambiguities will undoubtedly compound as continuing technological innovations permit online music services to provide offerings never contemplated during the legislative process.

The increased transactional costs (e.g., arguably duplicative demands for royalties and the delays necessitated by negotiating with multiple licensors) also inhibit the music industry's ability to combat piracy. Legal music services can combat piracy only if they can offer what the “pirates” offer. I believe that the majority of consumers would choose to use a legal service if it could offer a comparable product. Right now, illegitimate services clearly offer something that consumers want, lots of music at little or no cost. They can do this because they offer people a means to obtain any music they please without obtaining the appropriate licenses. However, under the complex licensing scheme engendered by the present Section 115, legal music services must engage in numerous negotiations which result in time delays and increased transaction costs. In cases where they cannot succeed in obtaining all of the rights they need to make a musical composition available, the legal music services simply cannot offer that selection, thereby making them less attractive to the listening public than the pirates. Reforming Section 115 to provide a streamlined process by which legal music services can clear the rights they need to make music available to consumers will enable these services to compete with, and I believe effectively combat, piracy.

The more time I have spent reviewing the positions taken by the music publishers, the record companies, the online music services, the performing rights societies and all the other interested parties, the more I have become convinced that I was right last year when I told you that ' As a matter of principle, I believe that the Section 115 license should be repealed and that licensing of rights should be left to the marketplace, most likely by means of collective administration.' (7) The Copyright Office has long taken the position that statutory licenses should be enacted only in exceptional cases, when the marketplace is incapable of working. After all, the Constitution speaks of authors' exclusive rights.

Compulsory licenses should only be instituted as a last resort, when the marketplace has failed. We cannot say that the marketplace has failed with respect to reproduction and distribution of nondramatic musical works because the marketplace has never been given a chance to succeed. The moment the copyright owner's right to control mechanical reproductions of a nondramatic musical work in the form of phonorecords was created, it was accompanied by the compulsory license, and at a time when the phonograph industry was in its infancy. Perhaps it is finally time to find out, for the first time, whether the marketplace is up to the challenge.

I believe that the preferable solution is to phase out the compulsory license to allow for truly free market negotiations. Such a course of action would address the two themes that I have already identified as central to the current crisis: the conflicting demands made by copyright owners' agents for the licensing of performance rights and by their agents for the licensing of reproduction and distribution rights, and the contrast between the ability of performing rights societies collectively to license performance rights for virtually all nondramatic musical works and the inability of any organization or combination of organizations to do the same with respect to reproduction and distribution rights.

Legislation is necessary to address these and other problems that hinder the licensing of nondramatic musical works. We have tried the regulatory approach, and it has failed. Perhaps it has failed because of insufficient regulation: if Section 115 were to be expanded to encompass a blanket license for all (or at least many more) uses of nondramatic musical works, at rates to be established by a mechanism similar to that which is employed with the other statutory licenses, record companies and online music services might finally be able to obtain the right to offer what consumers are clamoring for, and to provide appropriate compensation to composers and music publishers for the exercise of those rights. Last year I tried in vain to guide the interested parties to consensus on such a proposal, and I would not be disappointed to see such a proposal be adopted. Unfortunately, I do not believe the various parties will be able to reach a final agreement on such a proposal; if it is to be enacted, it most likely will have to be because you have concluded that it should be enacted notwithstanding the objections of some or all of the interested parties.

In the world of music licensing itself we have a model that does not involve a compulsory license and that works very well. The performing rights organizations manage to offer licenses to perform publicly virtually all nondramatic musical works that anyone might want to license for public performance. They offer such licenses on a blanket basis for those who wish to have the freedom to perform any work within a performing rights organization's repertoire. Currently, no similar mechanism exists with respect to the reproduction and distribution of phonorecords of nondramatic musical works.

I believe that we can take the model that works so well with respect to performance rights and use it for the licensing of reproduction and distribution rights as well. Existing problems in locating someone who is authorized to license the reproduction and distribution of a particular song presumably would disappear if the performing rights organization that is authorized to license the public performance of that song could also license the reproduction and distribution of that song.

I do not mean to hold out the performing rights organizations as paragons in every way. In fact, the second fundamental problem that I have identified — the demands made by both licensors of performance rights and licensors of reproduction and distribution rights that a music service obtain a license from each licensor for the same transmission — is caused by the often questionable demands of the performing rights organizations as well as those of the publishers' representative for licensing reproduction and distribution rights. But the true cause is what has become an artificial division of the licensing functions for nondramatic musical works. Why do online music services have less difficulty obtaining licenses for digital transmissions of sound recordings? Because the right of public performance and the rights of reproduction and distribution are now artificially split between two different licensors. For historical reasons (and, in at least one case, because of an antitrust decree), the performing rights organizations have licensed only public performance rights and the Harry Fox Agency has licensed only reproduction and distribution rights. That may have worked in the past, but it in the present — and most likely, even more in the future — it is an impediment that should be removed because it does not serve the interests of the songwriter, the publisher, the record company, the online music service, or the consumer.

As always, my focus is primarily on the author. The author should be fairly compensated for all non-privileged uses of his work. Intermediaries who assist the author in licensing the use of the work serve a useful function. But in determining public policy and legislative change, it is the author - and not the middlemen - whose interests should be protected.

A Legislative Solution

My proposal, tentatively entitled the 21st Century Music Reform Act, addresses many of the above-identified problems and attempts to strike the appropriate balance between the rights of copyright owners and the needs of the users in a digital world. The overarching purpose is to remove the statutory barriers which presently inhibit the music industry's ability to clear rights in order to open the licensing structure to free market competition.

This proposal effectively substitutes a collective licensing structure for the existing Section 115 compulsory license. It accomplishes this by setting forth rights and obligations for the newly-defined music rights organizations (“MRO”). The basic defining characteristic of an MRO is that it is authorized by a copyright owner to license the public performance of nondramatic musical works. But in fact, the proposed legislation would authorize the MRO to license the reproduction and distribution rights as well.An MRO would be authorized, and required with respect to digital audio transmissions, to license the reproduction and distribution rights of any nondramatic musical work for which it was authorized to license the public performance right. This structure creates an efficient mechanism for copyright owners to license and for potential licensees to obtain all of the necessary rights to make nondramatic musical works available to the listening public, particularly in the context of the Internet and other digital transmission media. It also leaves evolving business terms to the flexibility of marketplace negotiations. The proposed legislative text is attached as Appendix A and a detailed section-by-section analysis is attached as Appendix B. A brief summary follows below.

As indicated by the definitions section, existing performing rights societies ASCAP, BMI and SESAC would automatically become MROs. Other entities may also become MROs if they obtain the necessary authorization from a copyright owner. An MRO that is authorized to license public performance rights in nondramatic musical works would also be authorized to license reproduction and distribution rights for phonorecords of the same works. Moreover, any MRO would have to offer, as part of its license to perform publicly a nondramatic musical work by means of a digital audio transmission (e.g., an on-demand stream), a non-exclusive license to make phonorecords of that work (including server and other transient copies) and to distribute phonorecords of that work (e.g., downloads) to the extent that the exercise of such rights facilitates the public performance of the nondramatic musical work. This “uni-license” type of approach solves one of the major problems affecting the music industry today, namely whether certain types of digital transmissions (e.g., “pure” streams, on-demand streams, tethered downloads, and “pure” downloads) implicate the public performance right and/or the reproduction and distribution right and if so in what proportions. Because the royalty recipients of both rights are ultimately the same — music publishers and songwriters — this is in essence merely a valuation and accounting issue more appropriately left to market forces rather than legislative fiat.

A copyright owner could not authorize more than one MRO to license the right to a particular nondramatic musical work at any given time. That is essentially what happens today with respect to the public performance right. This provision is necessary for the efficiency this proposal seeks to foster. By having only one MRO authorized at any time to license a particular nondramatic musical work, the prospective licensee can more efficiently identify which MRO it must contact to obtain a license, and the MRO can more easily calculate and account for the royalties owed to the copyright owner and any other applicable parties.

Existing performing rights societies currently provide lists of the works for which they offer licenses. My proposal encourages MROs to continue this practice by predicating the MRO's recovery of statutory damages for the infringement of a work on the MRO having made publicly available a list of the works it was authorized to license; such a list must have included the infringed work at the time infringement commenced.

I recognize that at least one performing rights societies, ASCAP, may be prohibited by current antitrust consent decrees from carrying out the functions of a MRO as contemplated by this proposal. Because it is so important to the efficient operation of the marketplace that a licensee be able to acquire all necessary rights to a nondramatic musical work from a single source, the proposal effectively abrogates any provisions in existing consent decrees which would not permit a MRO to license public performance, reproduction and distribution rights. However, the legislation would not affect the other provisions of the antitrust consent decrees; for example, the provisions providing for a rate court to resolve impasses over rates for public performances would not be affected. Perhaps the most contentious issue — and one that I do not propose to resolve — is whether the antitrust decrees might be expanded to take into account the new functions of the music rights organizations. I know that publishers and prospective licensees have reacted in very different ways to that statement, and I would like to take the opportunity to clarify that I take no position on whether the existing consent decrees should be extended to, for example, the royalty rates offered by a MRO for a reproduction and distribution license to review by a rate court. I assume that the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice would have a major say in such a decision. Because this is such a contentious issue, it may be that its resolution should be part of any final legislative enactment.

MROs would also be authorized to license downloads and other reproductions made in the course of digital audio transmissions, even when there is no public performance involved. This should lead to “one-stop shopping” for any online music service seeking to license rights to a work. (8)

The remaining portions of the proposal clarify the rights enjoyed by parties other than MROs. Copyright owners of course retain the ability to enter into direct licenses on whatever terms to which they choose to agree, as they always have. Nothing obligates a copyright owner to utilize a MRO, but the increased efficiency of that structure provides an incentive for them to do so, just as they have all utilized performing rights organizations. Copyright owners may also authorize as many entities as they wish to license mechanical rights (other than those involved in digital audio transmissions) for their nondramatic musical works.

I recommend that the effective date for this proposal be as soon as is reasonably practicable. Existing performing rights societies appear to have all of the data and resources necessary to be effective and immediate MROs. The music industry needs relief quickly, especially if it is to compete against the popularity of illegal online music services. Although some delay might be necessary to allow the soon-to-be MROs time to implement administrative logistics, the period between the enactment and effective dates should be reasonably short. If it is, then the current system, even with its imperfections, can remain in effect without relatively drastic consequences or disruptions. If the delay is long, though, then new interim provisions would need to be developed. Constructing these interim provisions is likely to create further confusion and disruption in the music industry and should be avoided if at all possible. (9)

If this proposal is enacted, some licenses granted prior to the effective date will be incompatible with the post-enactment law. The final section of the proposal addresses these situations, and provides a sunset period for such licenses. For example, no one can use the statutory license to make phonorecords of nondramatic musical works after the effective date because the statutory license will not exist after that date. However, those who have lawfully made phonorecords before the effective date would receive a one year grace period to distribute their stock pursuant to the statutory terms in effect the day preceding enactment.

I recognize that if the proposal is enacted, some current music industry participants may have to adjust their business practices to maintain their current levels of profitability without the artificial rate ceiling afforded by the statutory license. Not meaning to minimize this practical reality, I wish to emphasize that the overriding goal of any licensing scheme should be to compensate copyright owners properly and provide an efficient and effective means by which licensees can obtain rights to make nondramatic musical works available to the listening public. Ancillary support organizations are important to the process, and will necessarily continue to serve their roles, albeit perhaps with some modifications induced by the increased competition present in a free market.

I also recognize that this proposal does not address some of the issues raised in the proposals that music industry representatives have recently submitted to you. Some of those issues relate to ringtunes, promotional uses, multi-format discs, percentage royalty rates, lyric displays, licensing of music for audiovisual works, locked content and accounting logistics. I consider these to be business or economic issues which are best resolved in the free market place. My proposal creates this market place, and I believe that there is no need for Government to legislate what the parties can negotiate themselves.

I hope that you will give thoughtful consideration to the approach embodied in today's proposal. We have only had the opportunity to discuss the proposal with the interested parties in the past few days, and I recognize that they have many questions and concerns. That is not surprising, given that the proposal represents a major change in the nondramatic musical works licensing regime. On the other hand, I am encouraged by the informal feedback I have already received from several music industry representatives supporting the basic concept of eliminating the Section 115 compulsory license in favor of an enhanced collective licensing system. I recognize that there may be many details that should be the subject of further discussion and consideration, but I believe the basic framework is sound. I look forward to continuing to work with this Subcommittee and any interested parties to craft a solution that maximizes the benefits for all concerned, whether along the lines suggested in my proposal or along the lines of the other proposals that you have been considering.

109th CONGRESS

1st Session

DISCUSSION DRAFT

To amend chapters 1 and 5 of title 17, United States Code, relating to the licensing of performance and mechanical rights in musical compositions.

IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

________, 2005

__________ introduced the following bill; which was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary

To amend chapters 1 and 5 of title 17, United States Code, relating to the licensing of performance and mechanical rights in musical compositions.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE.

This Act may be cited as the '21st Century Music Licensing Reform Act'.

SEC. 2. DEFINITIONS REVISED.

(a) Section 101 of title 17, United States Code, is amended by:

(i) deleting the definition of “performing rights society”, and

(ii) adding the following definition:

'A “music rights organization” is an association, corporation, or other entity that is authorized by a copyright owner to license the public performance of nondramatic musical works.'

(b) Section 114 of Title 17, United States Code, is amended by:

(i) replacing the term “performing rights society” with “music rights organization” in clause (d)(3)(C).

(ii) amending clause (d)(3)(E) to read in its entirety:

'(E) For purposes of this paragraph, a “licensor” shall include the licensing entity and any other entity under any material degree of common ownership, management, or control that owns copyrights in sound recordings.'

(c) Section 513 of Title 17, United States Code, is amended by replacing the term “performing rights society” with “music rights organization”.

SEC. 3. REPEAL OF COMPULSORY MECHANICAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE FOR NONDRAMATIC MUSICAL WORKS.

Section 115 of title 17, United States Code, is amended to read as follows:

'Sec. 115. Scope of exclusive rights in nondramatic musical works: Licensing of reproduction, distribution and public performance rights

'In the case of nondramatic musical works, the exclusive rights provided by clauses (1), (3) and (4) of section 106, to make phonorecords of such works, to distribute phonorecords of such works and to perform such works publicly, are subject to the conditions specified by this section.

'(a) Licensing of reproduction and distribution rights by music rights organizations. — (1) A lawful authorization to a music rights organization to license the right to perform a nondramatic musical work includes the authorization to license the non-exclusive right to reproduce the work in phonorecords and the right to distribute phonorecords of the work to the public.

'(2) A license from a music rights organization to perform one or more nondramatic musical works publicly by means of digital audio transmissions includes the non-exclusive right to reproduce the work in phonorecords and the right to distribute phonorecords of the work to the public, to the extent that the exercise of such rights facilitates the public performance of the musical work. A music rights organization that offers a license to perform one or more nondramatic musical works publicly by means of digital audio transmissions shall offer licensees use of all musical works in its repertoire, but the music rights organization and a licensee may agree to a license for less than all of the works in the music rights organization's repertoire.

'(3) No person shall authorize more than one music rights organization at a time to license rights to a particular nondramatic musical work.

'(4) A music rights organization may recover, for itself or on behalf of a copyright owner, statutory damages for copyright infringement only if such music rights organization has made publicly available a list of the nondramatic musical works for which it has been granted the authority to grant licenses, and such list included the infringed work at the time the infringement commenced.

'(5) The rights and obligations of this subsection shall apply notwithstanding the antitrust laws or any judicial order which, in applying the antitrust laws to any entity including a music rights organization, would otherwise prohibit any licensing activity contemplated by this subsection.

'(b) Other Licensing Agents. — Notwithstanding any authorization a music rights organization may have to license nondramatic musical works, a copyright owner of a nondramatic musical work may authorize, on a non-exclusive basis, any other person or entity to license the non-exclusive right to make and distribute phonorecords of such work in a tangible medium of expression but not by means of a digital audio transmission.

'(c) Direct Licensing by a Copyright Owner — Nothing in this section shall prohibit the direct licensing of a nondramatic musical work by its copyright owner on whatever rates and terms to which it agrees.

'(d) Definition. - As used in this section, the following term has the following meaning: A 'digital audio transmission' is a digital transmission, as defined in section 101, of a phonorecord or performance of a nondramatic musical work. This term does not include the transmission of a copy or performance of any audiovisual work.'

SEC. 4. EFFECTIVE DATE.

This Act shall become effective on ______________.

SEC. 5. EXISTING LICENSES.

(a) Any license existing as of [effective date] between a copyright owner of a nondramatic musical work or its agent and a licensee with respect to the right to make and distribute phonorecords of such work shall expire according to its terms or on [effective date plus 1 year], whichever is earlier.

(b) Any licensee that has made phonorecords of nondramatic musical works prior to [effective date] pursuant to the compulsory license then set forth in section 115 of this title may distribute such phonorecords prior to [effective date plus 1 year] according to the terms of the compulsory license existing prior to its repeal.

[Other conforming amendments to address other references in title 17 to section 115 will be necessary.]

21ST CENTURY MUSIC LICENSING REFORM

SECTION-BY-SECTION ANALYSIS

Section 1: Short Title.

This section provides that this Act may be cited as the “21st Century Music Licensing Reform Act.”

Section 2: Definitions Revised.

This section replaces the term “performing rights society” with the term “music rights organization” throughout the Copyright Act. This change in terminology reflects a fundamental function of this Act: to permit and require those entities that license the right to perform publicly nondramatic musical works to license as well the rights to make and distribute phonorecords of such works.

Subsection (a) in effect substitutes the new term “music rights organization” for the deleted term “performing rights society” by retaining the substance of the latter term's definition. The change in name reflects the additional functions, beyond the licensing of performance rights, that music rights organizations will perform pursuant to the amended section 115. Although the existing performing rights societies, such as American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) and SESAC, Inc. will transform into music rights organizations, the definition no longer specifically identifies these entities because additional entities — existing (e.g., the Harry Fox Agency) or new — may also become music rights organizations provided that they perform the functions described in the definition and required in the amended section 115.

Subsection (b) substitutes the term “music rights organization” in place of “performing rights society” in Section 114 of the Copyright Act. This conforming change is intended to have no effect on the substance or operation of Section 114. Subsection (b) also effectively deletes Section 114(d)(3)(E)(ii), the existing definition of “performing rights society” that is being replaced by the definition of general applicability for “music rights organization” set forth in Section 101.

Subsection (c) substitutes the term 'music rights organization' in place of 'performing rights society' in Section 513 of the Copyright Act. This conforming change is intended to have no effect on the substance or operation of Section 513.

Section 3: Repeal of Compulsory Mechanical Copyright License for Nondramatic Musical Works.

This section effectively repeals the existing Section 115 of the Copyright Act, including the compulsory license for making and distributing phonorecords (including digital phonorecord deliveries) of nondramatic musical works, by replacing the text in its entirety, and establishes the role of a music rights organization. It places certain conditions on the licensing of public performance, reproduction and distribution rights granted by Section 106 of the Copyright Act with respect to nondramatic musical works. These conditions do not apply to other types of works.

Subsection (a) sets forth the rights, obligations and limitations that apply to music rights organizations. The purpose of this subsection is to foster a consolidated licensing structure so that copyright owners of nondramatic musical works can license and users of nondramatic musical works can obtain in an efficient manner all of the necessary rights to make such works available, particularly in the context of the Internet and other digital transmission media.

Paragraph (1) provides that when a music rights organization has been lawfully authorized to license the public performance right in a nondramatic musical work, that music rights organization is also authorized to license the reproduction and the distribution of phonorecords of such work, including by digital audio transmissions. As a result, a music rights organization shall be empowered to license all rights relating to performance of the musical compositions in its repertoire and relating to the making and the distribution of phonorecords of those musical compositions. However, it does not follow that an entity authorized to license the making of phonorecords of a musical composition will necessarily be authorized to license the public performance of that musical composition.

Paragraph (2) obligates a music rights organization to offer, as part of its license to perform publicly a nondramatic musical work by means of a digital audio transmission, a non-exclusive right to reproduce phonorecords of the musical work and to distribute phonorecords of that work by means of a digital audio transmission, to the extent that such reproduction and/or distribution facilitates the public performance. Thus, for example, a music rights organization that licenses the public performance of a musical work by means of 'streaming' on the Internet must include within the license the right to make and distribute the incidental intermediate phonorecords created in the process of streaming, and the right to make phonorecords that reside on the licensee's server. A music rights organization may also choose to offer other types of licenses involving the reproduction and distribution rights, such as a traditional mechanical license to make and distribute phonorecords or a license to offer “downloads” of phonorecords of nondramatic musical works. Presumably, a music rights organization would elect at least to license all reproductions by means of digital audio transmissions, especially in light of assertions by the existing performing rights societies that downloading implicates the public performance right. This provision aims to alleviate some of the practical difficulties encountered in the present music licensing structure, which often finds licensees facing demands for separate licenses for the digital transmission of a musical composition from both a performing rights society and an agent for reproduction and distribution rights such as The Harry Fox Agency, while leaving as many issues as possible to be resolved by the private sector and marketplace negotiations.

Paragraph (3) ensures that no copyright owner of a work may authorize more than one music rights organization at any given time to license the rights to that work. This provision assists in achieving the efficiency this Act seeks to foster. Ideally, only one music rights organization should be authorized at any time to license a particular nondramatic musical work, so that the prospective licensee can more efficiently identify whom it must contact to obtain a license and the music rights organization can more easily calculate and account for the royalties owed to the copyright owner and any other applicable parties. In fact, as is the case with the existing performing rights societies, situations will occur in which more than one music rights organization may license the same musical work (e.g., a work written by two songwriters, one affiliated with ASCAP and one affiliated with BMI), but it is anticipated that those situations will be addressed in the same way they are addressed today.

Paragraph (4) encourages a music rights organization to make publicly available a list of the nondramatic musical works it is authorized to license in order to assist users of musical works in identifying whom they must contact to obtain a license. Most performing rights societies already maintain such a list on the Internet, and it is the intent of this provision that music rights organizations continue this practice. It behooves a music rights organization to update this list regularly, as the recovery of statutory damages is predicated on the list including the work infringed at the commencement of infringement, consistent with the policy embodied in Section 412 of the Copyright Act.

Paragraph (5) recognizes that some existing performing rights societies, which will become music rights organizations, are subject to judicially ordered consent decrees in antitrust actions which may prohibit the these entities from licensing both the public performance and the making and distribution of nondramatic musical works. For example, the current consent decree governing the activities of ASCAP prohibits ASCAP from “[h]olding, acquiring, licensing, enforcing or negotiating concerning any foreign or domestic rights in copyrighted musical compositions other than rights of public performance on a non-exclusive basis.” This paragraph abrogates any such provisions, to the extent necessary to permit a music rights organization to license both public performance and making and distribution rights with respect to nondramatic musical works. However, it is anticipated that all other provisions of the existing consent decrees will remain in place, and it is possible that the consent decrees will be modified to take into account the new functions of the music rights organizations. For example, it may be that the music rights organizations' setting of royalty rates for reproduction and distribution will be subject to the same type of review by the ASCAP and BMI “rate courts” as is currently the case with respect to royalty rates for public performances. The legislation does not require that the consent decrees be modified; whether that occurs would be resolved in the ongoing antitrust proceedings.

Subsection (b) clarifies that even though a music rights organization may have been authorized to license rights to a particular nondramatic musical work, a copyright owner still retains the right to authorize any number of other persons or entities to license the mechanical rights in that work for the purpose of making and distributing tangible phonorecords, such as compact discs or audio tapes, but not for the purpose of digitally delivering a phonorecord to a consumer. In other words, licensing of rights for all digital audio transmissions of nondramatic musical works must be done either by a music rights organization or directly by the copyright owner.

The effect of subsections (a) and (b), when read together, is that a copyright owner may: independently license the rights to its nondramatic musical works whether or not a music rights organization or other entity has also been authorized to license some or all of the rights to such works; utilize one music rights organization to license both the public performance and the reproduction and distribution rights in such works; and utilize one or more agents to license the making and distribution of physical phonorecords of such works. However, a copyright owner who chooses to utilize a music rights organization to license public performance rights in a nondramatic musical work is required to authorize the music rights organization to license the reproduction and distribution rights to such work. A copyright owner may also choose not to license its nondramatic musical works at all, although such a decision presumably would not be an economically rational choice. The Act anticipates that a performing rights organization will become a music rights organization, unless it chooses to cease licensing the public performance of nondramatic musical compositions. Any other person or entity, including a music publisher or a licensing agent such as the Harry Fox Agency, may function as a music rights organization or, alternatively, as a licensing agent for mechanical rights to make and distribute physical phonorecords depending on the authority it receives from the applicable copyright owner.

Subsection (c) clarifies that a copyright owner retains the right to enter into direct license agreements with licensees for its nondramatic musical works on an exclusive or non-exclusive basis. Any authorization received by a music rights organization or other entity to license rights in nondramatic musical works must necessarily be on a non-exclusive basis, and such entity may therefore only grant non-exclusive licenses to its licensees. Nothing in this Act compels a copyright owner to license its work or to utilize a music rights organization or a licensing agent.

Subsection (d) defines a digital audio transmission for purposes of subsections (a) and (b).

Section 4: Effective Date.

Section 4 establishes _____________ as the effective date of this Act. The present Section 115, with its compulsory licensing scheme, will remain effective until such date. During the transition period before the effective date, performing rights societies and any other entities desiring to become music rights organizations may establish or expand their licensing capabilities in order to be able to perform the functions set forth in this Act, and copyright owners may take the necessary steps to authorize music rights organizations to perform their new functions and to afford them time to adapt to the demise of the compulsory license.

Section 5: Existing Licenses.

Subsection (a) recognizes that some licenses between copyright owners or their agents and licensees will be in effect on and continue after the effective date of this Act. Because those licenses currently are either compulsory licenses under the existing Section 115 or are voluntary licenses the terms of which are shaped largely by the provisions of the existing compulsory license, such licenses should terminate not long after the compulsory license provision itself has terminated. Subsection (a) provides that such agreements will expire no later than one year after the effective date of this Act, providing a transitional time period for parties to negotiate new terms in light of the new licensing scheme.

Subsection (b) recognizes that some licensees may have made phonorecords of nondramatic musical works pursuant to the statutory license prior to its repeal. This subsection gives such licensees a one year grace period to distribute their stock according to the terms of Section 115 of the Copyright Act as it existed prior to the effective date of this Act. The rates and terms of the statutory license shall throughout this grace period remain what they were on the day immediately preceding the effective date of this Act. It is anticipated that all licensees under existing reproduction and distribution licenses will obtain new licenses either from music rights organizations or directly from publishers or their agents.

1. My written statement to this Subcommittee on March 11, 2004, available at http://www.copyright.gov/docs/regstat031104.html, includes a comprehensive history of this compulsory license. See,Section 115 of the Copyright Act: In Need of an Update?; Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Courts, the Internet, And Intellectual Property of the House Comm. on the Judiciary, 108th Cong. 5-6 (2004) (statement of Marybeth Peters, Register of Copyrights).2. See, e.g., Section 115 of the Copyright Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-553, the Digital Performance Right in Sound Recordings Act of 1995, Pub. L. No. 104-39, and Final Rule, Compulsory License for Making and Distributing Phonorecords, Including Digital Phonorecord Deliveries, 69 Fed. Reg. 34578 (June 22, 2004).

3. Final Rule, Compulsory License for Making and Distributing Phonorecords, Including Digital Phonorecord Deliveries, 69 Fed. Reg. 34578 (June 22, 2004).

4. Letter of July 7, 2004 to Marybeth Peters from E. James Sensenbrenner, Jr., Lamar Smith, John Conyers and Howard Berman.

5. Letter of September 17, 2004 from Marybeth Peters to E. James Sensenbrenner, Jr., Lamar Smith, John Conyers and Howard Berman.

6. See, David Sinacore-Guinn, Collective Administration of Copyrights and Neighboring Rights: International Practices, Procedures, and Organizations § 17.9.3 (1993) (citing 45 countries which permit collective licensing organizations to license both rights, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Mexico, South Korea and Spain).

7. Section 115 of the Copyright Act: In Need of an Update?; Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Courts, the Internet, And Intellectual Property of the House Comm. on the Judiciary,108th Cong. 13 (2004) (statement of Marybeth Peters, Register of Copyrights).

8. It would be 'one-stop' shopping with respect to all of the necessary rights for all works in an MRO's repertoire. Of course, it would not be 'one-stop' for a licensee wishing to obtain rights to all nondramatic musical works. That licensee would need to obtain a blanket license from each of the MROs. But that simply reflects the current state of affairs with respect to public performance rights, and that state of affairs appears to be satisfactory.

9. While one might imagine that agreeing upon royalty rates for the 'uni-licenses' offered by MROs may take some time, there is no reason why a MRO could not issue a license subject to subsequent agreement on what the rate would be, perhaps with some dispute resolution provision, in order to permit the new system to get off the ground quickly. There is good reason to believe that online music services would be pleased to enter into such license agreements.

Home Contact Us Legal Notices Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)Casino Music Performance Proposal

Library of CongressCasino Music Performance Proposal Sample

U.S. Copyright Office

101 Independence Ave. S.E.

Washington, D.C. 20559-6000

(202) 707-3000

Casino Music Performance Proposal Examples

Revised: 01-Apr-2013